PATHWAYS TO HEALING

by Brieanna Charlebois and Petronella Duda

As we hit the 150th anniversary of colonization, the Truth and Reconciliation Commission's Calls to Action have once again been thrust into the spotlight. These calls to action, released in 2015, were created in an attempt to right past wrongs and help Indigenous communities heal from the legacies of residential schools.

The Yukon has become a leader in this movement, implementing many different programs and initiatives. In the following profiles we listen to six Indigenous people share their healing stories-- either their own or how they are helping others in their community heal.

HEALING THROUGH ART

MARY CAESAR

Mary Caesar is a survivor of Lower Post Residential School and a recovered alcoholic. She attended the Adaka Festival held annually in Whitehorse, to showcase her art and how it has influenced her healing journey.

Mary Caesar likes to tell stories through her art – some her own, others from her community. She says words sometime go through one ear and out the other, with art people are forced to pay better attention.

Caesar paints her past, her pain and her emotions in the hopes to connect and help heal others with similar experiences and to reach those who may not know or understand the horrors of residential school.

After leaving residential school, Caesar attended Malaspina Univeristy-College, now known as Victoria Island University in Nanaimo, British Columbia. She says it was not always easy for her to share her emotions through her art.

She recalls one professor constantly pushing her artistically. Each week when the class displayed their work, he would tell her that her art was lacking emotions.

Fed up, Caesar finally gave him what he asked for. She came back the following week with an unusual display that included barbed wire. She laughs saying she only got a B, but she was happy she finally created something genuine.

Caesar is happy to have shared her art at the Adäka Cultural Festival. While the festival can be a bit physically draining, she says her family keeps her motivated. Her son David and his family came to visit all the way from Ontario.

WAYNE PRICE

Wayne Price, master carver, , travels frequently between his home in Alaska and the Yukon, working with communities to facilitate their healing journeys through traditional Indigenous art forms.

Wayne Price is an artist and carver form Haines, Alaska. He is a recovered alcoholic, who also found his healing pathway by expressing himself through art. He also attended the Adaka Cultural Festival in Whitehorse. There, he showcased his healing dugout, a project dedicated to all Indigenous people who are or have suffered from drug and alcohol addiction.

Wayne Price and his wife Cherri live in this house in Haines, Alaska. It is the same house he grew up in.

Price attended the Adäka Cultural Festival earlier in July, he is now carving a paddle in preparation for another festival in Kake, Alaska.

Once the paddles are carved, they are then decorated in traditional paintings and then preserved with varnish.

Price says the Creator told him that every wooden chips that falls while carving a healing dugout canoe or totem pole represents an Indigenous person affected by alcohol and drugs. He adds that if individuals in the community felt that it resonated with someone they knew, they could write a name on one of the fallen chips.

Price says that when he was a child, carving made sense of a crazy world. He says it still makes sense that way.

Traditional tools.

WHITEHORSE HEALING PROGRAMS & INITIATIVES

Yukon has many First Nations programs and initiatives focused on healing the community. The Committee on Abuse in Residential Schools (CAIRS), The Council of Yukon First Nations and the Jackson Lake Wellness Team are three organizations that provide professional assistance for those combatting past trauma, battling mental health issues and addiction.

JOANNE HENRY

Community on Abuse in Residential School (CAIRS) is an organization that was established in 1997. It offers support and engaging programs for Indigenous people who suffer trauma from Residential Schools.There are no requirements to use the organization's services.

Joanne Henry was a Residential School student.

She first arrived at the Lower Post Residential School in northern British Columbia at the age of five. Unlike other students, she ate and boarded with her mother who had found work at the school after her husband’s death. At the end of the first year, Henry agreed to stay at the school after her mom found other work, not realizing that her situation would profoundly change without a parent to watch over her.

Henry spent the next several years at three separate residential schools, where she was abused and traumatized -- and yet, while she acknowledges the suffering that happened at the schools, she refuses to call herself a survivor. Her journey continues.

Today, Henry works for CAIRS, a Whitehorse-based initiative that almost folded in 2010. Henry fought to keep the program alive because she believes that the residual effects of trauma, like that associated with residential schools, will be present for many generations.

CAIRS does its best to create a warm environment-- the exact opposite of Residential Schools. Henry says they do their best to avoid triggers in attempt to create a safe space for clients to heal.

CAIRS caters to the interests of individual clients; colouring, beading and drum making are among the many activities offered by the organization.

Henry says that the TRC is just a start, but that the Calls to Action aren’t meant to be a check off the list. Healing will take many generations.

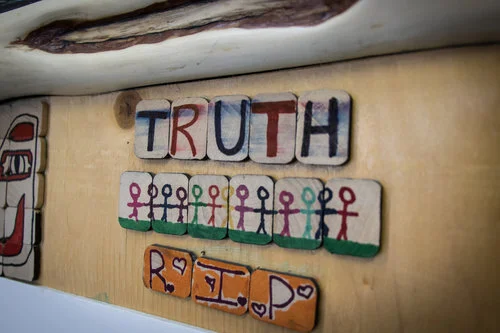

Healing is done through many ways. Here, Henry gazes up at a piece of art made by several members of different Indigenous communities.They find healing in creative collaboration, giving them a sense of community

INGRID ISAAC

Ingrid Isaac loves to dress in vibrant colours and designs that reflect her Indigenous culture.

Ingrid Isaac works as a resolution health support worker at the Council of Yukon First Nations. Although she did not attend a residential school herself, she helps counsel those who did, as well as individuals like herself who felt the secondary effects that have been passed down through generations.

For Isaac, every day comes with a fresh cup of coffee as well as a “fresh start”, according to her mug. She says she wanted a pink mug for quite some time, and when she finally went in search of one, this was the first she came across. It was perfect, she said. It fit in with her line of work as well as her own personal healing journey.

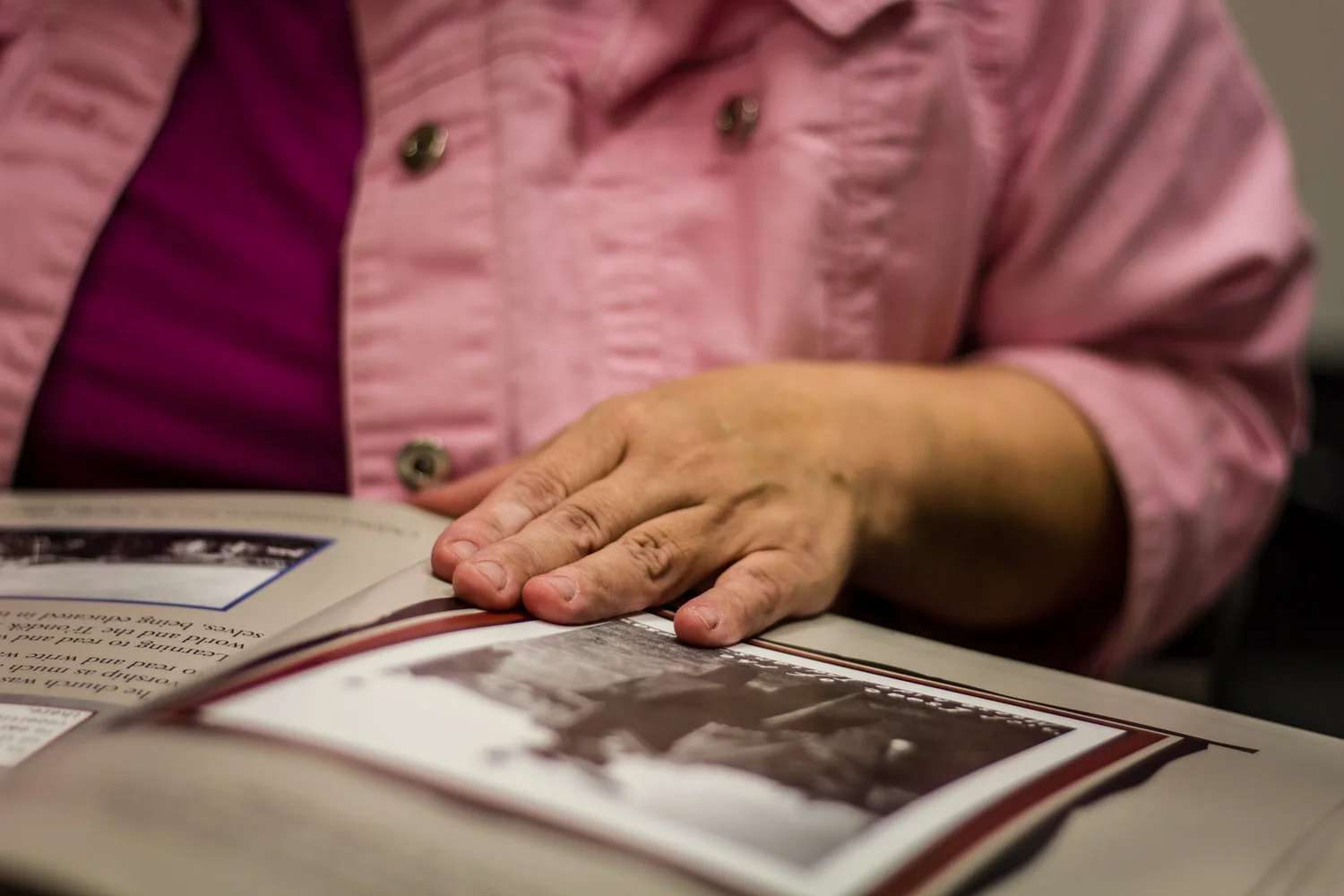

Isaac looks at a book on Residential Schools, using visual aids to show what life was like for these children

One day, after looking at a photo of herself from a work retreat, Isaac decided she did not like what she saw. She knew she had to improve her health, both physically and mentally, and adding colour into her life, through her clothing, was one way she wanted to accomplish that. Now, with both a colourful wardrobe and mindset, she says she feels much happier.

It took a long time for Isaac to realize that she had been negatively affected by the fact that her parents went to Residential School. She says she had to heal before she could help anyone else.

COLLEEN GEDDES

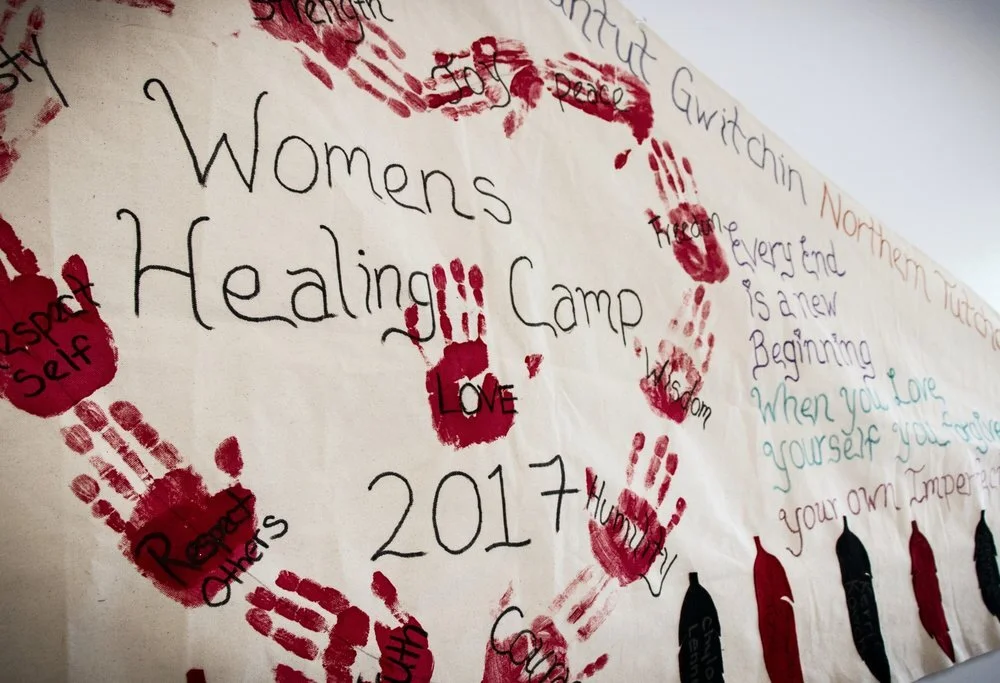

Colleen Geddes is the coordinator of the Jackson Lake Wellness Team, an organization aimed to combat addiction. While there is a strong focus on land and culturally-based healing techniques, programs also include clinical approaches. For the past five years, the team has conducted two month-long programs per year. The Healing Centre is located a half-hour outside Whitehorse on Kwanlin Dün’s traditional territory.

Currently Jackson Lake offers two camp programs each year; one for men and the other for women. Both Silverfox and Williams agree that program was life changing and that there needs to be more funding in order to provide more yearly camps

JACQUELINE JULES

Jacqueline Jules is a Registered Nurse at the Taiga Medical Clinic in Whitehorse. She is also Indigenous.

With only four staff members and 350 patients, the Taiga Medical Clinic was dreamt up only six years ago. It is the first of its kind in the territory treating trauma, mental health and addiction--all under one roof. However, the need for this sort of program is growing in Whitehorse; for outreach workers, psychiatrists and trauma training.

Taiga Medical Clinic is an innovative practice that helps bridge the gap between mental health and addiction services.

There is a clear lack of Indigenous people as medical practitioners. However, Jules is a First Nations RN and one of the four staff members at Taiga Medical Clinic.