Bridging the past and the future: Inside Tl’oo K’at’s fish camp

Meral Jamal

The head of a Chinook salmon smokes above a fire at the family salmon fishing camp. (Photo: Meral Jamal)

PROLOGUE

The motor goes quiet.

The boat comes to a halt.

The wind whipping through our hair dies down.

Robert Kyikavichik, Old Crow’s game guardian, leaves his seat and makes his way to the bow. Five passengers gently sway.

There is a stillness of momentary hesitation in the air. Whether it is the weather or our anticipation, we can’t tell.

Robert pulls the net out of the water and the world goes silent.

We’re all looking at his hands, wondering what he might grab from the net, hoping it might be the Chinook.

First, a piece of wood. Then, a piece of wood. A whitefish. And again, a piece of wood.

“Still no salmon,” Robert says, a look of disappointment crossing his face.

“They were supposed to be here by now.”

Robert Kyikavichik checks the fish nets for salmon along the Porcupine River. (Photo: Meral Jamal)

It is our second day in Yukon’s most northerly community. We are riding on the high that comes with getting a good night’s sleep and being young journalists eager to meet some of the people we’ll be spending the next nine days with.

We want to get talking, learning, listening, reporting. And we decide the best way to do this is to accept an invitation to meet some of Old Crow’s residents and take part in a family salmon fish and culture camp organized by the Vuntut Gwitchin government.

Nestled along the Porcupine River and accessible only by boat, Tl’oo K’at, which means “grassy place” in Gwich’in, is a spot for Old Crow’s young and old to sit around a campfire, heat coffee and roast marshmallows. It is also where the First Nation’s annual general assembly and the school’s fall caribou hunt take place each year. This summer members of the community came together at Tl’oo K’at from July 15-26 to celebrate something different: the beginning of the Chinook salmon run.

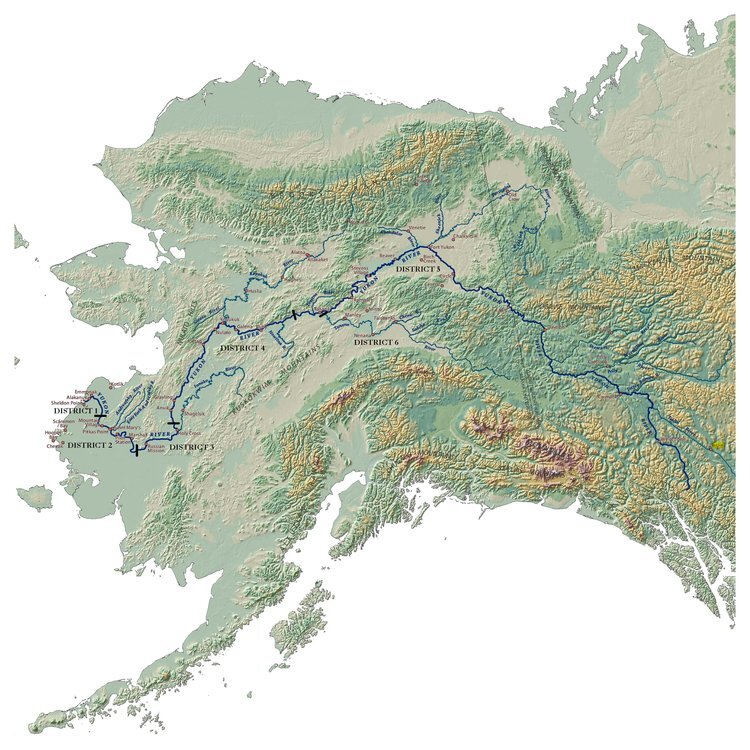

The Porcupine River is named after the Porcupine caribou herd which spends the winter months in the forested regions along the river before its annual migration to the calving grounds on the Arctic coastal plains. The Porcupine River begins in the Ogilvie Mountains in the Yukon territory and travels approximately 483 kilometres of Canadian waterway and 322 kilometres of Alaskan waterway, eventually joining the Yukon River near Fort Yukon, Alaska.

At the same time, the Porcupine River is an active trade route to the Yukon, but for the Vuntut Gwitchin, it also provides access to the Chinook and Chum salmon that travel upriver from Alaska from July through mid-October each year.

A PLACE TO TEACH, GROW, HEAL

The story of Old Crow’s family salmon fishing camp is the story for much of the programming that is happening in the community these days: it is a way for people to heal.

Natasha Frost, the manager of health and social programming with the Vuntut Gwitchin government — one of the departments that helped plan the fishing camp — says the camp is a way to get everyone together and get them talking.

“We try to implement camps because we are a First Nation community and a lot of the times when we get feedback from the community they want to go out on the land because the land is so healing to our people.”

Different departments have been working together to implement land-based camps since this spring, when the Porcupine caribou herd travelled through Old Crow.

“These are just strategies thought by leadership to heal our community and heal our people — get our people on the land doing what we’ve always done without strings attached, like working the stresses of day to day life,” Natasha says.

“We’ve had a lot of really hard things happen in our community with suicides and deaths, a lot of tragedy in the last bit, so a lot of our focus is how do we heal our people.

“We have a lot of suicidal ideation that happens. A lot of the issues that we face are related to mental health, substance use, grief, trauma.”

Here, at the camp, Natasha says people have been fishing, gathering together, eating and talking through their issues.

The filleted salmon is hung above the fire in the smokehouse. The scent of burning willow fills the air. (Photo: Meral Jamal)

When we arrive, we are fed first: hot coffee brewing in a blackened metal pot, sausages sizzling on a grate above the fire, whitefish and potato salad. A feast for kings and journalists.

Later, we find ourselves going around in an impromptu sharing circle, introducing ourselves and our families because that is how introductions are done around here: you are who your family is.

Charyl Charlie, director of education with the Vuntut Gwitchin government and fish camp organizer, joins the conversation. She sits opposite us on a bench overlooking the fire, all smiles from painting a slab of wood to be used as a swing by the kids at the camp. She is beaming as she tells us stories from the first day.

Charyl Charlie, director of education with the Vuntut Gwitchin government. (Photo: Meral Jamal)

“This time, we just thought that, with the kids, we’d bring them out here and get them to see what the salmon season is like on the Porcupine,” she says.

“It’s just to get them out into the camp setting, get them doing some traditional activities, and just enjoying the life — this remote lifestyle that we love.”

Charyl moved to Old Crow from Fort McPherson, N.W.T, to be with her husband when she was 19. What she loves most about Old Crow is what she loves about the camp: how everyone comes together. “It’s an isolated community,” she says.

“Just recently I thought about it, and what attracted me to Old Crow is kind of like the fishing camp. It’s a little community that works together. You’re either family or you’re distant relatives, and I like that community spirit where everybody helps each other.”

— CHARYL CHARLIE

For many of the residents of Old Crow, though, there is more to the camp than meets the eye. Tl’oo K’at seems to be the thread that connects the Gwich’in culture and the tradition of harvesting salmon to its youth — a bridge between the past and the future.

SAVING THE CULTURE

Robert works as the game guardian with the government during the rest of the year, but this week he is a helper at the camp, responsible for taking the kids to check the fish nets in his boat and showing them how to cut the fish when they’re brought back to camp.

For him, Tl’oo K’at is about more than just fishing and coming together.

Robert lights a cigarette. He stares into the distance, and begins talking about the past, sharing the stories of all those before him.

“Long ago, people used to come up this way and live off the land and get moose and fish and live season by season,” he says.

“In the springtime, we get caribou and … in the summer we change to fish, and then all of this goes back to caribou and moose to stock up the freezer for the winter, make sure that we always have food, traditional food on our table.”

A smile, and we are back in 2019.

“I enjoy doing things like this because you teach kids our culture, and the best place to do it is land based,” Robert says.

“Just taking kids out — teaching them our traditional way of life is really important and also education is really important too. They get both sides of the curriculum — traditional knowledge and that curriculum from school.”

“It’s important nowadays, you know, like people have to work and make money; people have to work to get gas to drive their boats. You can’t just make a living off the land anymore, you have to work to come out like this.”

— ROBERT KYIKAVICHIK

Robert Kyikavichik shows Old Crow youth how to fillet a freshly caught Chinook salmon. (Photo: Kanina Holmes)

The Gwich’in are one of the most northerly Indigenous peoples on the North American continent — only the Inuit live farther north. The Gwich’in are spread out in the interiors of Alaska, through northern Yukon, and in parts of the Northwest Territories.

According to the Gwich’in Social and Cultural Institute, Gwich’in total around 6,000 in all, with approximately 3,440 of them currently residing in the Northwest Territories. But in Old Crow, the population continues to remain between 250 to 280, the result of which is an urgent need to preserve the community’s culture and tradition.

The salmon camp is one way of doing this: for the people of Old Crow, preserving the culture means showing the next generation how to carry their tradition and way of life into the future.

The salmon — like the caribou — is a big part of this.

Louise Creyke, a social worker and support worker at the camp, agrees.

“Well, I think it’s unique to Old Crow in that it’s a way of life. It’s our tradition and culture that we’re trying to keep alive,” she says.

“It’s so nice to get away from town and to experience out on the land and just be without phones and without any technical stuff that we all seem to depend on when we’re at our office. We just seem to be so dependent on technology, and the camp is a good place to rejuvenate your spirit.”

When Louise isn’t talking to the kids or helping with the food, she can be found participating in a game of capture the flag.

She lives in northern British Columbia for the rest of the year, but spends her summers in Old Crow. There is something about the community that has people either coming back or staying put.

“We’re trying to instil it into the young people so they can have some grounding, and I find that even in my own life, I come home and I come back. My culture is really important and I get that foundation that sets me for challenges and other things in my life,” she says.

The Porcupine Salmon Plan

The Vuntut Gwitchin government developed and released the community-based Porcupine Salmon Plan earlier this year to address the ongoing concern of reduced numbers of Chinook and Chum salmon travelling the Porcupine River each year.

“This community-based salmon plan is one that reflects our traditional values, sustainability principles, conservation practices and we are committed to maintaining and forging partnerships to ensure our future generations have a traditional way of life with the salmon,” Old Crow’s Chief Dana Tizya-Tramm, says in the plan.

The plan will be revisited by the community every five years, and consists of three documents: 1) Local and Traditional Knowledge Report, 2) Porcupine River Watershed Salmon Restoration Plan and 3) the Implementation Plan.

The plan also discusses the use of science and research to increase salmon numbers, and the role the youth of Old Crow play in ensuring future harvesting.

“Like our way with caribou, we are salmon people too. Salmon that travel the Yukon River and then the Porcupine River into our traditional territory are integral to life for us as Vuntut Gwitchin,” the plan says.

SAVING THE YOUTH

Lindsay Johnston, the youth and recreation co-ordinator at the youth centre in Old Crow, says youth engagement in the community continues to remain a priority because of the emphasis the community places on the future.

“You’ll hear it from the elders constantly,” she says.

Old Crow, like many other First Nation communities, wants to engage and inspire youth to be active participants in the development of their land.

Lindsay says youth engagement rises and falls based on other things that are happening in the community, but this year it has been particularly low, which is concerning.

“I’ve been here for almost five years now, and I feel like each year there has been something that has kind of derailed things. It’s a mixture, like there was a year in the community we had seven deaths in the course of a couple of months, so that was nonstop the process of dealing with that and the grief.”

She says many people are grieving in the community, and it often takes longer for a small community like Old Crow to recover from grief and trauma.

The most recent loss of a youth to suicide in the community took place just a few weeks ago.

“It’s the culmination of a community that’s not really at the pinnacle of health and it’s trickling down in different ways — engagement is one of those.”

Lindsay says that in smaller communities, children often influence each other as well.

“I think up here in a small community, we run that challenge of not having enough numbers for sports teams, and the dynamic where just because my buddy doesn’t want to do it, I got my buddies here who are doing it, and so we do see that it’s small numbers of the same group of kids,” she says.

“It’s always the same group of kids always doing the same things, so one ring leader who doesn’t want to do something maybe hinders others who would want to engage.”

Sharing circle

Louise calls the circle for us, as visitors, to share our stories.

This time, all the kids are beckoned over to join the conversation.

We’ve spent part of the day talking to everyone at the fish camp, asking them about their stories — their childhood, their life in Old Crow. But this time, the tables have turned: Louise wants us — the journalism students from Ottawa — to tell everyone about our lives, our histories.

We go around, sharing our stories in a circle. The kids are shy, but it’s a start. We tell stories about life outside of Old Crow and outside the Yukon — life in all the other parts of Canada. The hour passes by faster than we expect.

In many ways, the future of Old Crow is in the hands of the youth of Old Crow. The survival of the community depends on how the kids choose to move it forward. The big question then, is how does the community develop the sense of responsibility some children are missing because of their disconnect from their own culture, tradition and land?

“I love the culture and I love everything about it, but I also always try to advocate for young people to step outside the box and take a look at where they want to go, what do they want to do — what do they want to bring back to their community and their people,” Louise says after the kids have gone back to playing.

“I hope I can inspire the young people. I am always talking about my life growing up here, my educational life, working in the school district and working with youth custody … and raising 23 foster kids. All the things to give kids the chance to think ‘wow.’”

We came into Old Crow looking to be inspired by the stories we find in the community. Little did we know our own stories might be inspiring to the kids of Old Crow too.

Louise also says the camp is a way to engage the youth of Old Crow in unique activities that they don’t get the chance to participate in otherwise.

“Yesterday, the young boys took a gun and went walking back to the lake. You don’t see 12-year-old kids in the city who do that,” she says.

“I think that kids learn life skills for sure — how to go to the kitchen and wash their own dishes — they’re expected to do that. They’re expected to clean their rooms, they’re expected to set a tent.”

Charyl says the camp is a way for the youth of Old Crow to learn other practical skills as well, such as keeping the camp clean, picking willow and driftwood to smoke the fish, and being bear-aware.

“They’re just helping with chores, and there’s different roles — if they’re asked to cut wood or pack wood or just to monitor the kids that are swimming at the shore or pack up gear that’s coming from the community,” she says.

“They’re also going to the net. They’re going with the fishermen to get the salmon with the net. And to see all of that — to watch it being cut and to actually cut it too — they can have that real life experience.”

At the camp, the kids are a force to be reckoned with. They are always eager, and they are always up to something. But for a community like Old Crow that has been around for thousands of years but is struggling to sustain itself because of the speed at which it is losing its culture and its tradition, youth engagement is something that needs to continue through the rest of the year too.

SAVING THE SALMON

The skies are changing as we near the evening. At this time of year the sun barely sets, but the intensity of the orange orb has diminished.

Robert’s son, Aidan, tugs the boat to shore and ties the ropes to the metal jutting out of the ground.

The wind is cool, and it is quieter by the water than it is at the camp with all the kids running around.

We have just come back from a round of checking the nets for fish. There is a quietness because there isn’t any fresh salmon yet. While it is called the salmon fish camp, the first day we are there, there is no salmon. There is whitefish and also a certain gloominess that comes with not finding exactly what you’re looking for.

But there is also the hopefulness that comes from believing that the land you are on will always find ways to take care of you.

When it comes to the salmon camp at Tl’oo K’at, there is the question of healing and of youth engagement, but there is also the looming question of the salmon themselves: how is the salmon camp to function without the salmon? And how does this affect everyone who is there? How does the community teach the next generation of Vuntut Gwitchin about the salmon when the population is under threat?

“I don’t know what’s going on,” Robert says to us.

“They’re counting a few salmon down below. They have a fish sonar … and they are counting a lot of fish there so I don’t know why we’re not catching them here.”

Chinook salmon run (photo: Teslin Tlingit Council)

Chinook salmon run (photo: Teslin Tlingit Council)

Downriver from Tl’oo K’at, a sonar station is monitoring the number of salmon coming up from Alaska.

At the station, there are two sonar systems in each side of the river, and each sonar measures approximately 40 metres each way. The systems run 24/7, recording the salmon passing by, which are counted on the computer by the sonar operators the next day.

So far, the numbers don’t look too good.

“I think in general the numbers are going down,” says Carly Weber, a wildlife technician and one of three people operating the sonar station.

According to the Yukon Chinook Strategic Stock Restoration Initiative report released by the Yukon Salmon Sub-Committee in 2016, between the early 1980s and the late 1990s, the run size of the Chinook salmon averaged 120,000 fish. Since 2010, the salmon numbers have declined to an average of 60,000.

“I think there’s an increased effort to monitor populations now because there’s a lot of harvesting and climate change,” says Carly.

“Today I talked to a gentleman, and he used to heavily net last year but he’s kind of taken a different approach on it, saying that instead of using his gas money to come check nets every day and actively catch salmon, he’s putting in a little more money into bringing food up here so he can let the salmon population replenish and not take too many out.”

Old Crow, unlike other Yukon First Nation communities such as the Tr'ondëk Hwëch'in, and the Champagne and Aishihik First Nations, has not suspended salmon fishing so far. According to the Porcupine Salmon Plan released by the Vuntut Gwitchin government, the community is in conversation about using six-inch mesh nets to let the bigger fish pass, using 50-foot long nets to allow for some passages, and limiting the amount of time in the water. But residents of the community say there should never be a closure, and that there should always be a fishery for Chinook and fall Chum on the Porcupine River because it is a constitutional right for the people of Old Crow to harvest.

With the future of the Chinook salmon under threat, however, more Yukon First Nations suspending salmon harvesting continues to remain a possibility.

THE FUTURE

It is our third day in Old Crow, and we decide to go back to the fishing camp. We find ourselves at the dock earlier in the day, eager to go back because of all that we experienced the day before.

When you are from a city, it is hard not to be mesmerized by the simple joys that come with being out on the land. Especially when it is land that promises berries and caribou and salmon.

We recognize a shift in the atmosphere before we even reach the shore. The air is different — it is charged with electricity, and we don’t realize it till we get to the camp, visit the smokehouse, and find eight beautiful salmon smoking.

“Somebody gave us five and we caught three,” Robert says to us, livelier than ever because of his catch.

Everyone is in good spirits.

Anna Taureau is at the fish camp with her daughters. It’s a family affair. She lives in Old Crow but is from the charter community of K'asho Got'ine, formerly known as Fort Good Hope, N.W.T, and this is her first time learning about how the people of Old Crow cut and smoke salmon.

Everyone — the young and the old — gets a shot at cutting the salmon, but it is Robert who leads the way.

Robert says he learned how to cut salmon from his Gwich’in friends down in Alaska. There is something in the way he sharpens his knives and moves his shoulders — he is an artist with a paintbrush.

“They’re quiet and watching and you know, learning,” Robert says of the kids.

“You can tell they’re all soaking it into their brains because they’re quiet and paying attention. If they were in town they’d be all sidetracked and doing other things, but up here as soon as you say you’re going to go and cut fish they all go and watch you.”

Anna learns to filet the fish too, excitement and eagerness radiating off her.

“I feel really happy and really blessed that my kids are learning, and I’m learning and getting to show them,” Anna says.

“When they do get older, they’ll get to learn how to cut fish and learn from the best.”

Later, we find ourselves by the fire once again, stuffing smoked salmon in our mouths and talking over each other in between bites. When we get a minute, we catch a breath and gulp down more salmon.

What began as a good day became a great day, and perhaps that is the magic of Old Crow and its Chinook.

EPILOGUE

Tl'oo K'at encompasses a battleground for three profoundly important struggles: saving the salmon; saving the youth of Old Crow; and saving the culture and traditions of the Vuntut Gwitchin. These three challenges are as complex as they are interconnected.

No one knows what the future holds. Not on any of these fronts.

What we have discovered is both concern and hope.

Questions surrounding the health of the salmon population still swirl. But there is also optimism that these fish will return, just like the caribou did in the spring this year. And there is also faith the land will provide for people as it has done for millennia.

“It’s up to nature to take its course,” Robert says when we’re walking back to the camp from the shore.

Questions about the youth of Old Crow and how they will carry the culture and tradition of the Vuntut Gwitchin forward remain a concern for the adults in the community too.

“You could just tell it’s something that’s in their DNA,” Louise says when the kids try their hands at cleaning fish.

“I know they’re comfortable in their environment and I think they’re just comfortable with who they are.”

Louise is also hopeful about the future.

“We’re all always in this state of change, but I always come home to settle myself here,” she says.

“My hope is that I can bring my children and my grandchildren to a place like this.”

As for Robert, he says he loves being out on the land and in the water way more than he enjoys being in town. He is a quiet man, but when he talks about the camp, his face lights up.

What is culture, if not the land you come from? What is identity, if not your culture?

Like most of Old Crow, you cannot tell where the land ends and the people begin. They are one and the same.

Magic late-summer sunset over Old Crow (photo: Kanina Holmes)

Credits: Some photos supplied by Clare Duncan and Kanina Holmes

Editor’s note: Interviews and information for this story were gathered during a community stay in Old Crow from July 13-25, 2019.