Living off the land: What the Porcupine caribou mean to the Vuntut Gwitchin

Sarah Sibley

People in Old Crow enjoy snacking on dried caribou. (Photo: Sarah Sibley)

William Josie remembers standing inside the community centre talking to a few out-of-town guests when he heard someone yell.

It was the long weekend in May and the annual Caribou Days festival was underway. Josie walked out of the centre, stepped over a few broken eggs that had been dropped by competitors playing a friendly game, and rushed to the banks of the Porcupine River right outside.

Caribou. Several of them. They were swimming in the ice-choked river.

“It was a good feeling,” says Josie. “There was a buzz around the community hall.”

For the first time in three years, the Porcupine caribou were back in Old Crow.

Lorraine Netro recalls that day well too. She’s a member of the Vuntut Gwitchin First Nation and a longtime advocate for the Porcupine caribou.

“It really impacts our well-being as Gwitchin people,” she says. “People were so very happy ... and you could just see it and feel it in the community. You know, we've struggled over the past number of years.”

OLD CROW, HOME TO THE PEOPLE OF THE LAKES

Located 128 kilometres north of the Arctic Circle, Old Crow is the most northerly community in the Yukon. It’s one of 19 communities in Alaska, Yukon and the Northwest Territories that are dependent on the Porcupine caribou. In fact, the Vuntut Gwitchin strategically chose to settle in Old Crow because it was along the herd’s migration path.

“That's really where a lot of our power comes from, is from our brother, the caribou,” says Chief Dana Tizya-Tramm of the Vuntut Gwitchin First Nation.

The Porcupine caribou is at the centre of Vuntut Gwitchin First Nation culture and tradition. For tens of thousands of years, caribou and salmon, from the nearby Porcupine River, have fed and sustained them.

An Old Crow landmark, this antler pole sits outside the home of Stephen Frost, an elder in the community and a renowned hunter. (Photo: Sarah Sibley)

People hang caribou and moose antlers outside their houses in Old Crow, showing their pride and respect for the animal. (Photos: Sarah Sibley)

After the caribou is caught the task of stripping, cutting, smoking, drying and cooking begins. Slabs of caribou meat make their way into stews, sausages, jerky and countless other dishes. It’s stored in freezers to enjoy for months to come.

Every part of the caribou is used in some way. Bones are boiled and used for soup, and the bone marrow consumed in dishes such as Ch'itsuh or pemmican. The head of the caribou, considered a delicacy, is cooked for special feasts, usually roasted over a fire or placed in a soup. Hooves are boiled into a jelly or hung and dried to use as chimes during a hunt, making hunters sound like the animal they’re tracking.

Hides are tanned and used for moccasins, gloves, jackets, mittens and other pieces of clothing.

Caribou jerky after it has been dried in a smokehouse. (Photo: Sarah Sibley)

These caribou ribs will be further butchered and cooked. (Photo: Sarah Sibley)

This bowl of soup contains chunks of caribou meat. (Photo: Kanina Holmes)

These keychains and jewelry pieces are made from caribou hide and antlers. (Photo: Sarah Sibley)

The Porcupine caribou has the longest land migration of any animal, travelling over 2,400 kilometres each year, according to the Canadian Parks and Wilderness Society. The trek can stretch over Alaska, Yukon and the Northwest Territories.

Usually, people in Old Crow see the herd in April or May and again in August or September.

But over the past several years, the caribou have not returned to the community, forcing hunters to travel up to 150 kilometres up river to hunt. It means more money spent on gas and more time on the hunt.

There are several theories as to why the caribou have strayed away from Old Crow.

Josie says it has to do with changes related to ice thickness. Caribou look for lichen to eat, so when there are wet conditions during the fall in Old Crow and the ground freezes sooner and thicker than usual, the caribou alter their route. The lichen also has the potential to freeze and become trapped in the ice, leaving a limited food supply for the caribou.

Tundra fires are also cited as a problem. Fires have destroyed lichen, so the caribou look elsewhere, according to a 2014 report about climate change-related effects on the caribou in Alaska and the Yukon.

Temperatures in the territory have risen at a faster rate than the rest of Canada, according to a 2017 auditor general’s report on climate change. In 2016, the Yukon’s average temperature was over 3 degrees Celsius higher than the average for the years 1961 to 1990. Nationally, it climbed 1.7 degrees Celsius.

GETTING CARIBOU MEAT

Josie says a bull can produce up to 136 to 227 kilograms (300 to 500 pounds) of meat depending on the age and size of the animal. He says it takes an average of four caribou to sustain his family between the winter and spring harvests. People in Old Crow harvest a total of anywhere between 100 to 150 caribou a season.

Kathie Nukon’s family did not get any caribou this spring.

“It's really difficult because it's nice to have a steak from the store, but I would prefer to eat caribou or fish,” she says.

Caribou meat cannot be bought at a local grocery store under the terms of the Porcupine Caribou Harvest Management Plan. It’s an effort to prevent and combat over harvesting.

In the store in Old Crow, a package of beef sirloin tip roast weighing 1.4 kilograms, (just over three pounds), can be upwards of $38, an expense Nukon says is not affordable for many people in the fly-in community.

Joseph Tetlichi, chair of the Porcupine Caribou Management Board and a member of the Vuntut Gwitchin First Nation, says there are three communities in the Northwest Territories that have not seen caribou for five years.

They rely mostly on moose, he says. They are also focusing more on trapping smaller animals such as duck, rabbit and geese. This means people must expend more energy to obtain the same amount of food.

“It’s nice to have a steak from the store, but I would prefer to eat caribou or fish.”

Josie says not everyone has the capability or the equipment to participate in the hunt, so experienced hunters harvest extra animals and share them. Most hunters are only free on the weekend because they have other jobs, he adds.

Between 1992 and 2008 there was a 38 per cent decrease in meat consumption in Old Crow, according to a 2018 report on sustaining Canada’s northern Arctic ecosystems and the livelihoods of Indigenous peoples who rely on them. The report suggests as employment numbers increase, caribou harvest levels will decrease.

In a culture focused on sharing, this presents a problem if there’s not enough caribou.

Many elders in Old Crow rely on family members or friends to obtain caribou for them. Some exchange hunting supplies in return for some meat, but many no longer work and the cost of supplies are very expensive.

Lorraine Netro says the community tries to band together to ensure elders who have been consuming traditional meat their whole lives are sustained, but this isn’t always happening.

“The saddest part, I think, (was) when we were not able to harvest caribou and there was not enough,” she says.

MONITORING THE HERD

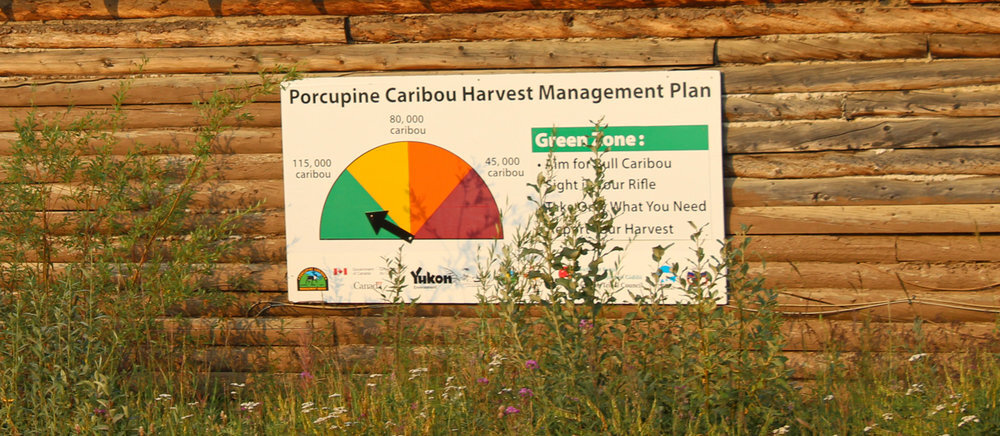

Residents of Old Crow have been required to report their harvest of Porcupine caribou since 2010, when the Porcupine Caribou Harvest Management Plan (PCMB) was first implemented. The plan is an agreement by the five First Nation governments to protect the herd by monitoring the herd’s size and population, and setting hunting restrictions as needed.

The plan has seen success, with the population of the caribou almost doubling over 10 years, according to Tetlichi.

The PCMB uses a scale to show the status of the herd, similar to a stoplight flashing green to red. Right now the scale is green, meaning the caribou population is a safe size and hunting does not need to be regulated.

Still, hunters are asked to adhere to a few rules, such as taking only what’s needed and targeting only bulls.

This year, the Vuntut Gwitchin, under the leadership of their recently elected chief, Tizya-Tramm, also took the extraordinary step of declaring a climate emergency. The community said changes to the climate are threatening their way of life and the relationship they have with the caribou.

People have been advocating for the protection of the herd since the 1980s. The Porcupine Caribou Management Board resulted from an agreement in 1985 between the federal and territorial governments with the First Nations communities that rely on the caribou. The board advocates for the caribou.

In the U.S., a highly contentious 2017 tax law supported by President Donald Trump could open up parts of the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge (ANWR), located in Alaska, for oil and gas exploration. The calving grounds of the Porcupine caribou lie in this area.

“If there’s oil and gas drilling in the core calving grounds of the Porcupine caribou, that’s going to absolutely destroy our way of life forever,” says Netro, who has spoken publicly on behalf of the Vuntut Gwitchin since the 1980s.

She says they won’t back down when it comes to the herd.

“Our voice is going to be at the forefront of this issue for all time. We will not compromise. We will not sacrifice the lifestyle and the way of life for our grandchildren and all future generations.”

THE NEXT HUNT

With the second caribou harvest of the year approaching in mere weeks, Josie says the community is prepared. Rifles, binoculars and knife kits have already been set aside.

“We’re always ready,” he says.

Every fall harvest, several youth get time off of school to join the hunters on the quest for caribou. The caribou they obtain will be harvested and prepared by other children in the school and used to feed students hot lunches throughout the year.

This fall harvest is crucial to ensure there is enough meat for the entire winter and early spring.

Netro says it’s important to get youth involved.

“They’re very concerned and they’re very worried about what their future is going to look like because they are hunters and trappers already,” she says.

Signs created by students showcase the importance of the caribou to the Vuntut Gwitchin people. (Photo: Sarah Sibley)

Lorraine Netro says it’s important to get youth involved because it’s their future. (Photo: Sarah Sibley)

With the caribou crossing through Old Crow already this year, Josie is hopeful the animals will come through the community again.

But he’s ready to travel far if necessary.

“Even if it’s a long distance away, in the summer, winter, we’re going to go look for them. Whether it’s way up Porcupine or Crow River, or in the winter with Ski-Doos, we’ll be looking for them wherever they are.”

Additional images provided by Kanina Holmes

Editor’s note: Interviews and information for this story were gathered during a community stay in Old Crow from July 13-25, 2019.