‘Our language is our life’: Revitalizing Gwich’in in Old Crow

Clare Duncan

Elizabeth Kyikavichik, 74, shows flash-cards of animals and their Gwich’in names to the children at her daycare. (Photo: Clare Duncan)

“Vadsaih, caribou.” “Negoo, fox.” “Zzoh, wolf.” “Nehtruh, wolverine.”

Elizabeth Kyikavichik flips through flash-cards with children at her daycare in Old Crow. This is part of the daily routine. The three-to four-year-olds sit in front of her and confidently recite the Gwich’in names of animals shown on the cards like they’ve done it a hundred times before.

Elizabeth gently corrects their pronunciations when needed, ensuring they elongate their vowels and shorten consonants.

She says she teaches colours, numbers, animals, and other simple nouns and verbs in Gwich’in to the children.

At this important developmental age, she says, children will relate a colour or a taste to an object before they know its name. In the same way, they can relate the Gwich’in word for the object and it helps them remember what it is.

One child can’t remember the word for rabbit.

“Geh,” Elizabeth reminds her, pronouncing the word as one abrupt syllable.

These basic words help them better understand life, she says.

Elizabeth, 74, is one of only 30 people in Old Crow’s population of 221 who officially speak the Gwich’in language.

This remote, fly-in village is the northernmost community in the Yukon, located 128 km north of the Arctic Circle. Old Crow is one of 11 Gwich’in communities across the Northwest Territories, Yukon and Alaska.

Using the language, Elizabeth says, connects the Vuntut Gwitchin people of Old Crow with the land. It helps translate exactly what needs to be said in a precise way, more so than English does.

Speaking Gwich’in, she says, makes you spiritually, mentally and emotionally healthier. It helps you survive.

“Our language is our life,” she says.

In all of Canada, just 295 people speak Gwich’in, according to 2016 Statistics Canada census data.

Gwich’in is on the 2010 UNESCO endangered languages list. It’s considered to be severely endangered, meaning the language is only spoken by older generations who don’t speak it to children or among themselves.

The year of Indigenous languages

The United Nations General Assembly proclaimed 2019 as the International Year of Indigenous Languages based on a resolution of the UN Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues (Resolution 71/178).

The observation of the International Year of Indigenous Languages by the UN aims to raise awareness of the consequences of the endangerment of Indigenous languages across the world, with an aim to establish a link between language, development, peace, and reconciliation.

Elizabeth is one person who has taken it upon herself to pass on the language to the next generation of Gwitchin children. The community is developing additional strategies to ensure the language is spoken by the entire family. It could mean Gwich’in would no longer be considered severely endangered.

One of the ways Old Crow is trying to revitalize the Gwich’in language is through developing a language program through the Vuntut Gwitchin First Nation government. This program is open to anyone who wants to learn, but is targeted at young adults, like Briana Tetlichi, who can then pass the language down to their children.

For the past year and a half, Briana, 25, has been working as the heritage language assistant, learning the language and being trained to teach the language at the same time.

THE NEXT GENERATION

“When people speak the language you can just tell the difference. People talk more. They laugh more. There's more emotion” — Briana Tetlichi

(photo: Clare Duncan)

Briana has been teaching Gwich’in to her one-year-old daughter since she was born. She names the stuffed animals by their Gwich’in names and teaches common expressions like “chiitaii ahchin,” it’s raining outside.

Briana says she’s not a fluent speaker of Gwich’in but that’s been her goal for as long as she can remember.

“I'm still a beginner and I'm still learning and I think I'll be a learner all of my life,” she says.

One of the barriers to learning the language, Briana says, is finding the time when everyone is so busy.

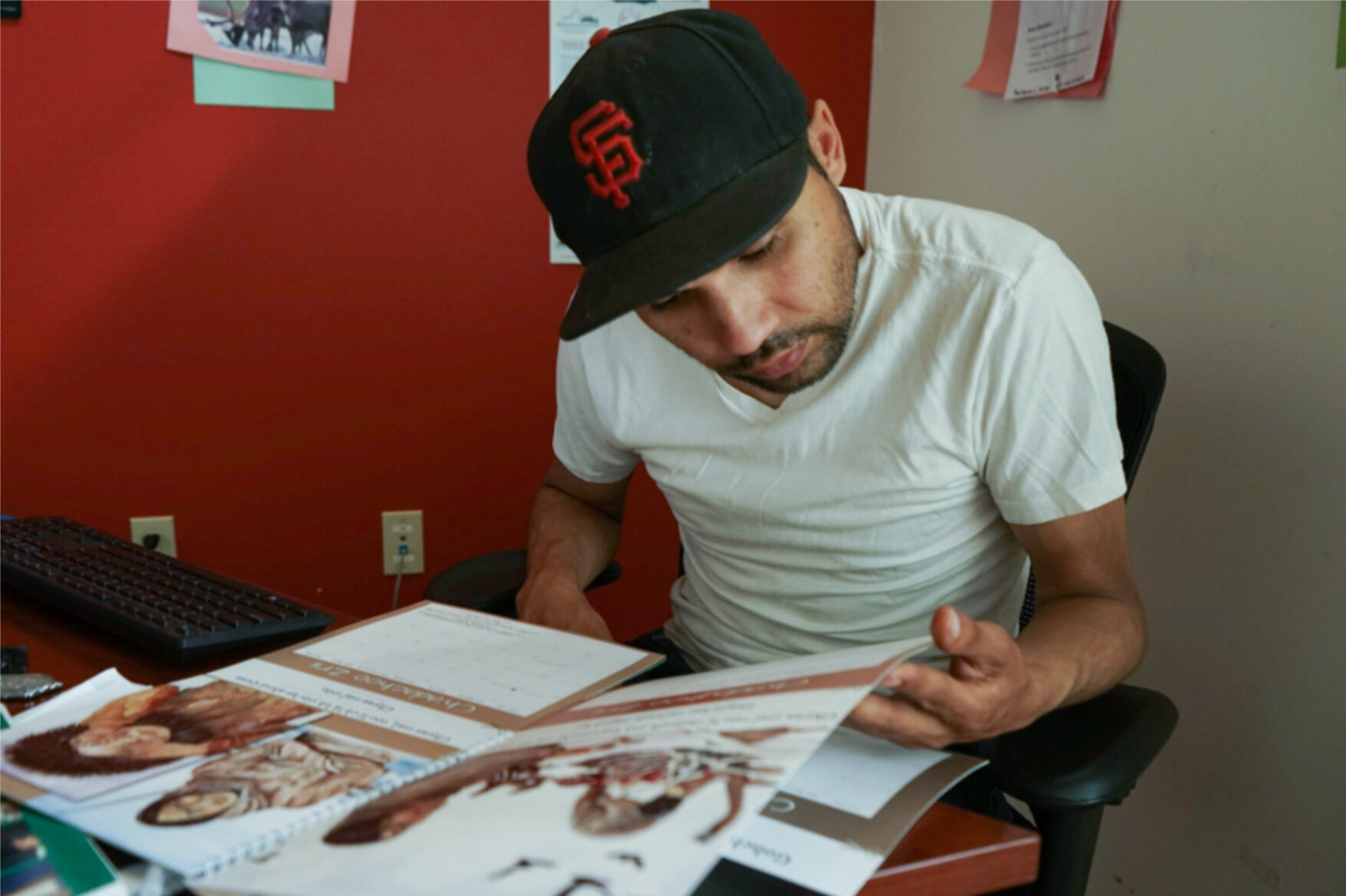

Brandon Kyikvichik reads a quote from Sarah Abel

Geetak dahshuk shih kwaa ts’at gweedhaa, googa dahthee shih gahana’yaa gwats’o’ geenjyaa, geenjyaa: “Sometimes there’s no food for quite a while, even that, right until they get something, they travel, they travel.”

As the language assistant, Tetlichi assists Sophie Flather, 26, the language co-ordinator of the Vuntut Gwitchin First Nation.

Her office is in the left wing of the John Tizya Centre, the heritage building in Old Crow. Quotes from elders in Gwich’in are postered to the walls.

Sophie sits at a computer at her desk, clicking through phrases of Gwich’in on a Word document. So far, she has created two textbooks for the program and is working on a third, with Briana’s help.

Sophie Flather, 26, is working on a third level of a Gwich’in textbook. (Photo: Clare Duncan)

To create the textbooks, Sophie says she prefers to work with fluent speakers, who are mostly elders. But she uses any tools and resources available.

Sophie’s main role is to plan and teach a method of language learning called direct acquisition. It’s designed to immerse adults in the language for six or more hours a week within a classroom environment.

Her goal for the program is to create more fluent speakers, people who can use Gwich’in in their daily lives. Her vision is to see people raise their families in the language.

Like learning any language, she says, it takes many hours of practice.

Children learn the language in school, but in order to become fluent, they need to be able to speak it outside of school as well, she says.

Sophie says there is a growing interest in the community to take the course and learn the language for their kids. More people are asking about classes, wanting to take the classes, and taking an interest in teaching, she says.

“A lot of the time people hear me speaking [Gwich’in] and then they’ll be more invested in the program because they see that I’m progressing and learning,” she says.

She started the program three years ago. The first year, she worked on curriculum development. The second year, there were two graduates from the introductory course. This past year, there were five.

“There have been growing numbers. I think at the beginning people weren’t too sure what it was, but the community is getting a little bit of a better idea of what it's about. I think they do believe in the way that it's being taught and that it can be effective,” she says.

A NEW APPROACH

“Our people created this language and we've been speaking it for thousands of years. It's how we do everything, it’s how we survived” — Sophie Flather

(Photo: Clare Duncan)

Learning the language is meaningful for Flather, she says, because, “our people created this language and we've been speaking it for thousands of years. It's how we do everything, it’s how we survived.”

She recalls a time when an elder told her that if you learn the language you’re going to be happy all of the time. Laughing, she says it’s true.

Sophie doesn’t have any children yet, but says she would love to raise her family in Gwich’in and see them want to pass on the language as well.

Elizabeth Kyikavichik’s nephew, Brandon Kyikavichik, 34, learned the language when he was young, hearing it all his life from his family.

Juk kwat tyaa gweendoo dinjii ch’ihtak googa akoo deedi’yaa gadhan kwaa: “But really, nowadays not even one person has the skills to do what they did [back then]”

Brandon Kyikavichik reads a quote from Sarah Abel

He sits in an armchair in his living room. Lighting a cigarette, he says he remembers the final days of when elders spoke only Gwich’in, what he calls “the very bitter end” of an era.

The community meetings, meals, religious services, “every hymn they sung, every sermon they gave, it was all in Gwich’in and I saw the last of that. That's probably my fondest memory of the language, remembering hearing those elders speak it. It was beautiful,” he says.

“The very essence of who we are as a people is encoded in our language. We are an ancient and beautiful culture. And when the language dies a lot of who we are as people is going to die with it.”

LEARNING GWICH’IN

“I know how hard the government fought to eradicate and destroy our language and the fact that there are still people speaking it today is so empowering and inspiring” — Brandon Kyikavichik

(Photo: Clare Duncan)

When Brandon went to Whitehorse for high school, he says he never spoke Gwich’in because he had no reason to in the city, but once he came back to Old Crow he started using it more.

Now, he says he uses it mostly at work and with other fluent speakers. He laughs, recalling how people like to tease and joke around with each other in Gwich’in. He says speaking it is very playful and fun.

But he says he doesn’t use it often enough.

Brandon has been working as the cultural interpreter at the heritage centre with a mentor who helps him translate and transcribe audio recordings of elders telling Gwich’in stories. He says he writes what the elders say and his mentor converts the Gwich’in into English.

They collect these stories so that they are accessible for future generations. He says the community can use these translations for curriculum, legislation, and even inspiration.

In May, the Vuntut Gwitchin First Nation government used a quote he had worked on when it declared a climate emergency.

The declaration, titled “Yeendoo Diinehdoo Ji’heezrit Nits’oo Ts’o’ Nan He’aa,” translates to “After our time, how will the earth be.” This quote was derived from a story from elder Sarah Abel.

Brandon Kyikavichik reads a quote from Sarah Abel

Yeendoo diinehdoo ji’ hee zrit nits’oo ts’o’ nan hee’aa?: “After our time, how will the earth be.”

Brandon appreciates his one-on-one learning experience.

For the Gwitchin people, he says, “we don't learn by somebody giving long drawn-out explanations about things. We learn specifically by doing.”

Language translation isn’t part of Brandon’s job description as a cultural interpreter, but he enjoys doing it and believes it’s important. (Photo: Clare Duncan)

Sophie says the mentor-apprentice approach is an effective methodology, but only under the right circumstances. The elders are busy and don’t always have time to help.

She likes the immersion methodology she’s using because it’s more accessible for a larger number of people. This way, she’s learning as she’s teaching and bringing people along the same path with her.

Learning and teaching the language is also a way the community is trying to heal from the intergenerational trauma of residential schools.

Children were removed from their communities and families and strapped, beaten and ridiculed for speaking Gwich’in. For some older fluent speakers in Old Crow today, the language is a trigger of shame and embarrassment.

Brandon’s mother went to residential school.

“Everything we're doing is all about trying to get over that,” he says. “All the programs we're doing, even just me just going and hanging with the elders and talking Gwich’in with them and making them laugh, that's a part of it too.”

He pauses.

“Everything we do is just trying to fix what they broke.”

Elizabeth Kyikavichik was able to relearn Gwich’in after attending residential school. She says she never lost it because “it’s in my DNA.”

Brandon says, “I know how hard the government fought to eradicate and destroy our language and the fact that there are still people speaking it today is so empowering and inspiring.”

The trauma that comes with speaking the language is one barrier, but Brandon says there are other social barriers when it comes to sharing it.

“Quality of life lends itself to saving the language. If we don't have proper education, we don't have proper training, we don't have proper health care, we don't have proper housing, it’s gonna be more difficult to accomplish the things we want to accomplish,” he says.

What is it going to take to turn things around for the language?

“Everything we have in our heart and soul,” Brandon answers without hesitation. “And that might not even be enough.”

Brandon Kyikavichik reads a quote from Myra Kaye

Yeenoo dai’ ndoo tr’eedaa, gogoontrii, ndoo tr’eedaa t’oonch’uu: “Long ago we moved forward, it was difficult. We moved forward, that’s how it was.”

When he speaks about Gwich’in, his elbows rest on his knees, his hands are loosely crossed over his chest like he’s holding it in his hands, close to his heart.

Speaking the language “doesn’t just make you feel better and happier, it empowers you,” he says, pounding his fist into his other hand.

For Sophie, the language holds the Gwitchin people’s culture and world view. It’s how they relate to each other and to the land. If Gwich’in was lost for good, the people would lose all of this knowledge and wisdom attached to it.

At this point, language classes are held only during the school year for a couple of months at a time. Sophie says the program could be more effective if she is able to teach year-round without taking a break for the summer.

“Right now we just don't have the capacity to do that. We’re trying to create more teachers,” she says.

In August, she’ll get help with the curriculum when some of the people behind the technique of direct acquisition come to Old Crow. Sophie’s program is based on the Paul Creek curriculum, which was developed at the Salish School of Spokane in Washington to teach the Indigenous language of Nsyilxcn.

The method of direct acquisition is also being used to teach Tlingit, a language spoken in the Pacific Northwest of North America, including Carcross and Teslin in the Yukon.

Sophie says she’s hopeful that Gwich’in won’t be lost.

Briana is also hopeful, firmly stating, “I don't even want to think about that. I haven't thought that.”

She smiles when she talks about speaking and hearing the language.

“When people speak the language you can just tell the difference. People talk more. They laugh more. There's more emotion,” she says.

Briana says when people speak Gwich’in, you can tell the difference because there’s more emotion. (Photo: Clare Duncan)

Briana also hopes that her daughter will be one of many Gwich’in speakers of the next generation.

“It's empowering to take our language back and to be able to speak it. It feels so good to speak the language. It's part of who we are. It's part of our identity.”

[Aii] eenjit zrit tr’igiikhii goo’aii zrit diiyehjuu nadizhii kat nizii ji’ gqizrih zrit gook’iighe’ duuleh tr’igwiheendaii juu chan gwinuu: “That’s why we speak of them at times, so that our future generations, if they’re good, through them we will live on. That’s what they say.”

Brandon Kyikavichik reads a quote from Sarah Abel Vagwandak

Editor’s note: Interviews and information for this story were gathered during a community stay in Old Crow from July 13-25, 2019.